If you ask what is the most popular racing championship in the US, the answer, of course, will be only one – NASCAR. Why 4 kilometers is a lot, from whom mechanics hide wheel nuts, and how NASCAR does without telemetry, read in the photo report.

Our Russian colleagues from Motor visited the Brickyard 400 stage at the iconic track in Indianapolis. The first thing they encountered was the smell in the pits of racing teams. Instead of gasoline or oil, NASCAR smells like food. And the food, the most American that neither is – burgers, french fries and sunflower oil – this is the aroma that walks all over the paddock. And for the guys who work in the heat, mechanics roll cars filled to the brim with drinks around the pit lane instead of carts with tires.

In terms of popularity, the races of the top division Sprint Cup are second only to American football matches – baseball and basketball were defeated more than 5 years ago. The NASCAR Daytona 500 and All-Star Race have settled into American culture side by side with the annual Super Bowl broadcasts and Thanksgiving football games. The reasons for the growth of the NASCAR audience are not only the spectacle of the races, in which 43 drivers continuously fight each other for a good four hours, but also the special character of the racers.

NASCAR participants do not go into their pockets for words, they joke well, often swear and do not hesitate to sort things out with the help of fists or pokes on the side of an opponent’s car. Simplicity in NASCAR attracts, unlike sleek Formula 1 drivers or overly intelligent golfers, Sprint Cup racers personify the average American who works the whole week, and on his legal day off is not averse to having a drink.

To be honest, calling the main US racing championship “NASCAR” would not be entirely correct. NASCAR is the National Stock Car Racing Association that runs multiple series at the same time. A feature of American racing is the possibility of participation of pilots in several divisions at once.

All these championships are united not only by oval circuits, but also by the relative cheapness of participation. For example, a competitive Sprint Cup team needs about $20 million per season, while Formula 1 requires about $200 million.

Legacy from the past

Not the last role is played by adherence to traditions: NASCAR does not care much about improving technology, relying more on habit and attractiveness for the audience. So until 2011, carburetors were used, and direct fuel injection appeared only this season. The main innovation was the ability to collect data on the condition of the car after the race. Yes, you read that right: until last season, NASCAR teams simply raced cars without telemetry and limited themselves to communicating with the driver. The cars received an electronic engine control unit, but full-fledged telemetry in the spirit of Formula 1 is still very far away. Even motor oil is a generation behind INDYCAR and Formula One.

Refueling

Forget about filling machines, here the tanks are filled from heavy canisters, which are hand-carried from the boxes. Due to the impressive weight of the cylinders, the strongest guys become “refuelers”. During a stop in the pit lane, they need to fill the tank of the car with the contents of two canisters, but due to the lack of modern telemetry, the teams do not know exactly how much fuel the pilot has in the car.

One of the highlights of NASCAR is correctly calculating how much fuel the pilot will get. The process goes like this: the “stables” know how much an empty cylinder weighs, before refueling, the mechanics weigh the filled cylinder, and after that, the spent one. Approximately representing the consumption on one circle, engineers calculate tactics.

Pit stops in NASCAR take an average of 13-15 seconds, given that in most cases, drivers prefer to change two wheels at a time. Parallel changing of four wheels is prohibited, so if the team has serviced, for example, the right side of the car, mechanics can run around the body of the car and take care of the left. Formula 1 uses one wheel nut, NASCAR uses four. To speed up the process, in the Sprint Cup, the nuts are smeared with special glue.

The fan is always right

The fans here are treated with great attention, like customers in American stores, “always right.” They have endless autograph sessions, pit lane walks, and sometimes “fan homage days” where drivers interact with fans and even serve them drinks.

However, this rapprochement has a downside: the audience, accustomed to the fact that they are welcome everywhere, began to borrow equipment from the teams. For example, when walking along the pit lane, many wheels are left unattended in the open air, fans can, on occasion, unscrew a couple of nuts. When a loss is discovered at a pit stop,

time has already been lost – the team can only hastily look for spare nuts or install other tires.

In order to stop this practice, NASCAR began to cover discs with cardboard circles.

Tires

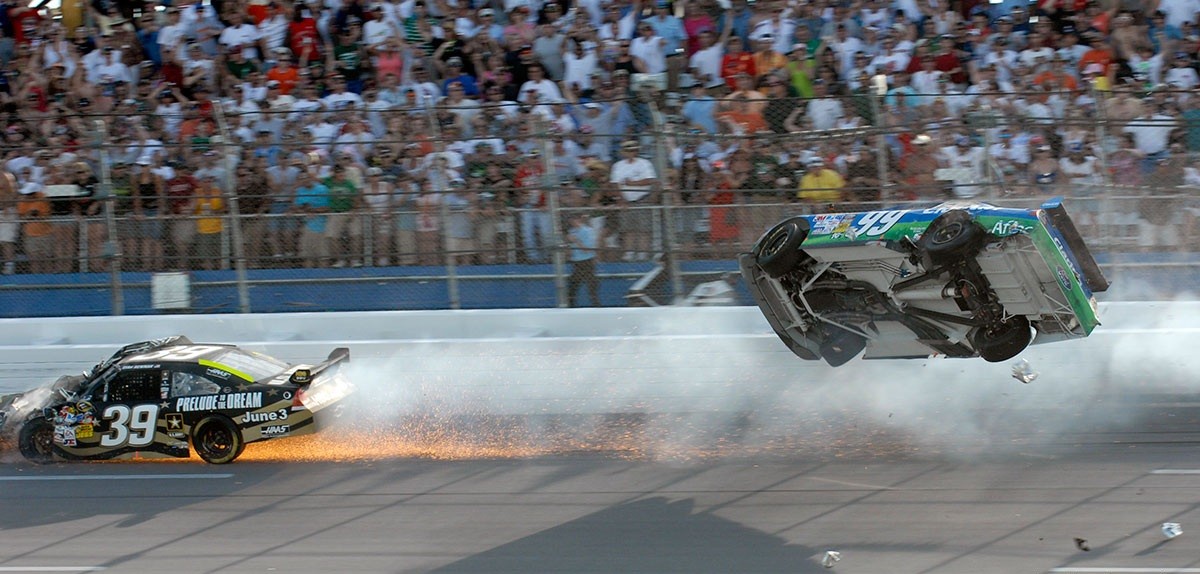

Formula 1 fans will remember the Indianapolis Motor Speedway scandal in 2005, when due to the increased wear of Michelin tires, most of the teams refused to participate in the race. A similar incident occurred at IMS in 2008 in the NASCAR series. Sprint Cup monopoly tire supplier Goodyear was unprepared for the debut of a new generation of cars on the track in Indianapolis with its protracted turns.

The increased load on the tires led to the fact that the rubber only lasted ten laps, after which the tires exploded. As a result, the pilots had to constantly change the wheels: by the time of the pit stops, the tires were worn out to the very cord. In order to prevent unjustified risk, the administration of the championship threw out yellow flags every ten laps, giving the pilots the opportunity to safely visit the pits. By the end of the race, the riders had used every tire Goodyear brought to Indianapolis.

Grand Prix Day

The pilots’ parade in front of the Brickyard 400 starts at 12:30: from that moment on, the show program on the track does not stop for a minute. After driving a lap around the circuit, the pilots give interviews that are broadcast on large screens, and then get behind the wheel and rush to the starting line. Here, after the next interview, a traditional minute of silence is announced in memory of the victims of accidents on race tracks and military conflicts in hot spots.

The starting grid in the European sense of the term does not exist in NASCAR. Before leaving for the installation circles, the cars line up one after another along the wall.

After the cars start the engines, the audience’s headphones are filled with radio communications from the pilots. And while Juan Pablo Montoya was complaining to his engineer that he couldn’t hear anything, the audience could hear the engineer, Montoya himself, and all the other participants perfectly.

The busy schedule is another feature of the Brickyard 400. In “regular” NASCAR races, drivers can have a barbecue in between races or relax while watching a football game broadcast.

In Indianapolis, everyone has to work. Any “windows” in the schedule go to the discussion of settings and communication with the press and fans – and this component in America has been elevated to the rank of a cult. Each driver must come to the VIP guests of his team and devote about half an hour to questions from the category “how fast can a NASCAR car accelerate” and “what is the number of the car your partner has”. However, such conversations do not bother anyone.

By Sprint Cup standards, the four-kilometer Indianapolis Motor Speedway is an unnecessarily long circuit. Most NASCAR races take place on ovals ranging in length from 800 meters to 2.4 kilometers: the passage of such a circle takes about 20-30 seconds. At IMS, the pole position time was about 50 seconds: during this interval, the audience has time to get bored.

Greg Biffle in the Ford Fusion: “It’s hard to overtake here because the track is very narrow. All the turns here are flat, and the speeds on the straights reach 205-208 miles per hour – in such conditions, it is more profitable for pilots to stay behind the opponent than to try to get ahead of him, because as soon as you catch up with a competitor, your car immediately loses the advantage in speed. In this case, two pilots begin to move in parallel – and an aerodynamic bag immediately forms behind them, into which someone else strives to get. Then this third one is built into the same line as the first two – and you get a situation where the cars go side by side, but still cannot overtake each other.